Here at the south pole, we have some of the cleanest air in the world. As a result, a lot of unique atmospheric research goes on here, mainly at NOAA’s Atmospheric Research Observatory, nicknamed ARO. A few days ago I had the opportunity to be taken on a full tour of the observatory by scientist Kelliann Bliss, who explained to me how it all works:

[JD]Thanks for your tour of the NOAA Atmospheric Research Observatory the other day. It’s really quite incredible that such a complete lab is positioned here at the South Pole. Why does NOAA have an observatory here at the south pole? What’s the significance of this particular spot?

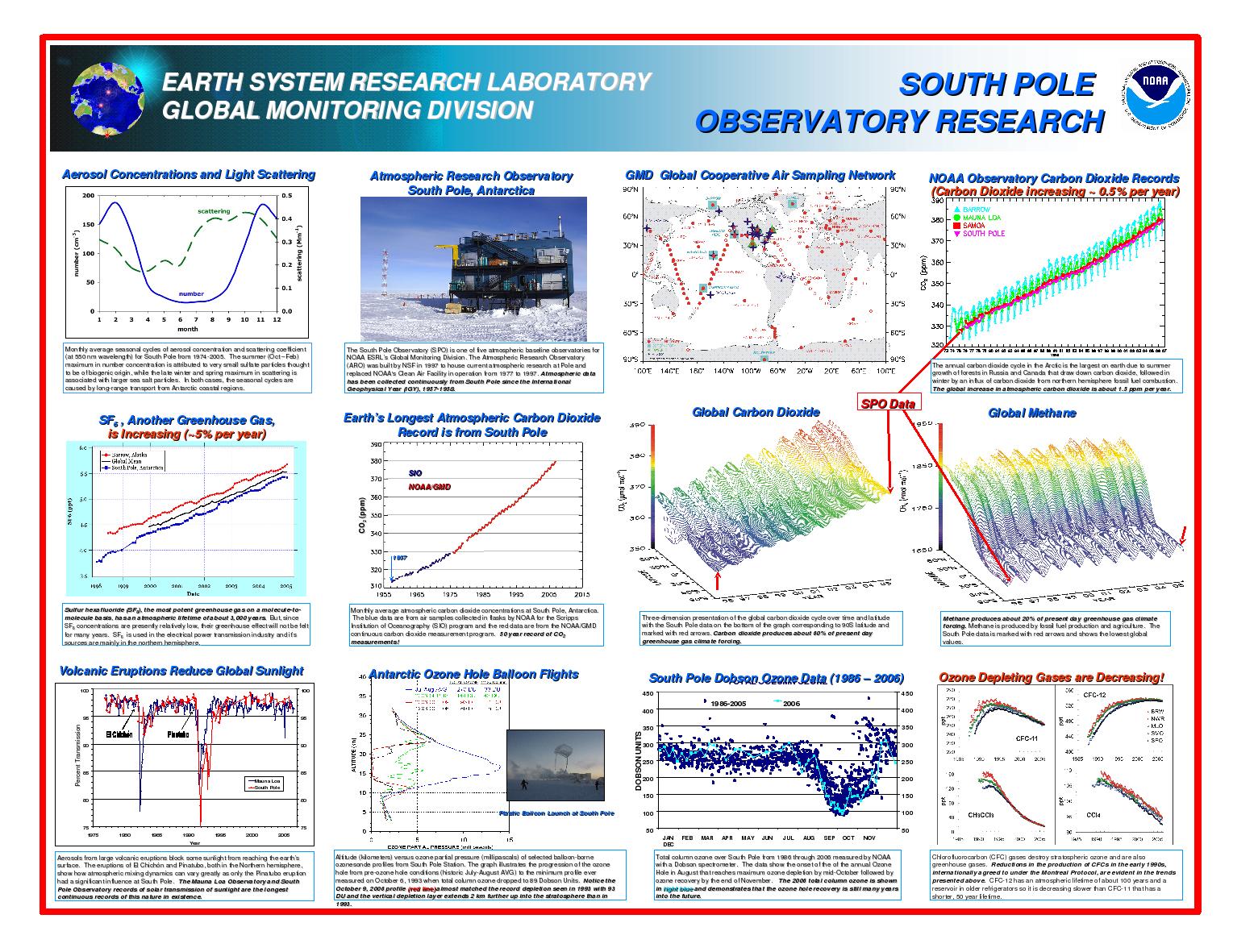

[KB]This station is part of NOAA’s Baseline observatories. We now have six in Barrow, AK; Trinidad Head, CA; Mauna Loa, HI; Pago Pago, American Samoa; South Pole and the newest is a joint project with the NSF in Summit, Greenland. The idea is that by having these spread out across the globe in relatively clean areas (atmospherically speaking) then we can get an idea for the background (baseline) of the planet. We can use that information to then go into a city and say well yes, we know this is “dirty”, and this is why. This data is part of the info that people use to try and figure out how much the planet is changing over the years as well, how much of it is caused by human influences. This is also some of the data they have been referencing in the summits on climate where countries have been getting together and trying to set limits of things to meet in future years (which so far hasn’t been working).

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jamfan2/8375187538/in/photostream

Life down here is harsh – it’s sunny 24/7 during the summer, and the temperatures are very very cold. What challenges unique to Antarctica do you come across while performing your scientific work here? Any particular things that need to be considered here and nowhere else in the world?

One thing for certain is because it IS so cold is that we have to have special cables (sadly way more expensive) as normal power cables just so they don’t get brittle and break. Lubricants that everywhere else we’d put in instruments to help them move smoother here can’t be used as they freeze and bind up the instruments even worse than if we used none (so we don’t use any). There is also the problem with accessibility. We do some flask sampling as well as the continuous in-situ sampling. Once the station closes for the winter those flasks have to sit here and wait to be shipped back to Boulder, CO until the station opens again. There is also the fact that if something breaks and we don’t happen to have replacement parts then we are either stuck with a broken instrument or we improvise, get creative and ask for new parts to be sent when the station opens again. In some respects it is not unlike what astronauts have to do if they don’t have parts.

Could you give me a brief overview of the main types of science that goes on at ARO?

We are measuring the atmosphere, and what chemicals are doing; CO2 (several different ways),over 60 greenhouse gases such as halocarbons,CFCs (actually these were ozone depleters until they were banned in 1992). We also measure ozone four different ways, aerosols, black carbon, UV, and the sun’s radiation as it relates to the planets temperature.

What’s your particular role with NOAA and ARO? I’ve seen you around the station occasionally in a uniform – is NOAA military? How does that work?

I am an officer in NOAA Corps, the way I generally describe it (partially in jest) is the seventh branch of the uniformed service that no one has ever heard of. NOAA Corps came into existence when during WW1 members of the Coast and Geodetic Survey were surveying foreign ports and were being captured and tried as spies as they wore no uniform. The uniformed division was put into place to protect them and the valuable work they were doing in creating charts and some maps of areas. To be accepted to NOAA Corps you must have a degree in some science, engineering, or mathematics, then there is a lengthy application process, training is basically going through OCS with the Coast Guard with a great deal of seamanship and ship-handling added onto the side. As for the majority of new officers the first assignment is to a research vessel as a deck officer. This is a small service there are around 340 of us right now and we are all dedicated to furthering science and research and scientific policy. The particular billet that I am in right now here at the South Pole is that of the Station Chief of the Atmospheric Research Observatory. They usually have one officer and one civilian stationed down here at the pole and the idea is that the civilian is usually the tech person and good with fixing things and the officer is generally the “scientist” though I put that in quotations as the real scientists are the PhDs back in Boulder and we work with them to get the data they need in a manner that doesn’t compromise quality but still adheres to the challenges we have at such an extreme site.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jamfan2/8375194814/in/photostream

How long have you been doing your job here? In the time you’ve been working down on the ice, what stands out as some of the more interesting observations, measurements, or events that you’ve witnessed?

I have only been here since November this year, and I spend 8 months in Boulder, CO training with the scientists before coming down here. One of the more interesting things is to realize that our instruments are sensitive enough to pick up the CO2 you exhale as a spike in the data if you happen to be upwind of the inlet tubing. The other great thing is seeing how excited people get about the information when they come to get a tour. I think we are doing great, important science here and it makes my day when people get thoughtful when they learn something they didn’t realize. Everyday, non-scientist people are the best way to get the info out there that there is a problem, the CO2 has been steadily rising since we started taking records here at the Pole in the 70’s (and is much higher than we’ve ever seen in ice cores from other stations), or that the ozone hole isn’t just some random theory, it’s something we can show graphically!

Thanks Kel!

Previously, Kel showed me how she takes ozone measurements.

Comments

One response to “Touring the South Pole Atmospheric Research Observatory with NOAA’s Kelliann Bliss”

[…] NOAA Atmospheric Research Observatory